David Binney, 'South' (2003)

At the end of Playing Changes is a list: The 129 Essential Albums of the Twenty-First Century (So Far). I organized these by year, and then alphabetically by artist name. I'll be running them down here, in that order. (No one appears more than once as a leader, though there’s ample overlap in personnel.)

My earliest recollection of seeing alto saxophonist David Binney is from 1998 or so, just after I moved to New York. He was playing at The Internet Café, a narrow, sweaty room in the East Village that had about as much cachet and charm as the name would suggest.

Binney was there with a band called Lan Xang, which he formed with tenor saxophonist Donny McCaslin, bassist Scott Colley and drummer Jeff Hirschfield. I'd admired the group's self-titled debut, released in 1997 on Binney's own label, Mythology Records. The sound of the band in close quarters — by which I mean McCaslin had the bell of his tenor in my face — was a visceral thrill, even if some others in the room were obviously there to check their email.

I came to understand that self-determinacy is a hallmark of Binney's artistic profile, along with the compulsion to hybridize. By the early 2000s I was seeing him regularly at the 55 Bar and Cornelia Street Café, always with a terrific band combining volatile heat and a sleek feeling of lift.

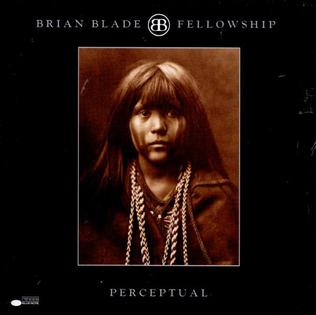

One such group featured Chris Potter on tenor saxophone, Uri Caine on piano, Adam Rogers on guitar, Scott Colley on bass and Brian Blade on drums. They recorded an album called South for ACT Records in 2000, though it took a few more years to see release in the United States.

The album is a hyper-articulate postbop sprint, with every member of the group functioning at his peak — and pointing in the general direction of future bands like Chris Potter's Underground and the Donny McCaslin Quartet (more on those later). Listen here for the braided, dark-hued saxophone lines, for the tidal swell of rhythm, for an inexorable forward pull at every moment, with every move.

South is available for purchase at Amazon, or can be streamed on Spotify.